What did the Dayton Accords do?

1. Most importantly, the Accords froze the military confrontation and prevented it from resuming.

This eventually lifted the siege of Sarajevo. By this time, over 100,000 people had already been killed in the war.

The Peace Plaza monument in Dayton, Ohio (CC-BY-SA)

2. They stopped the massacres of civilians and ended the campaign of rape against women.

3. They caused the remaining detention camps to be dismantled.

4. They retained Sarajevo as an integral part of Bosnia-Hercegovina — as its capital, not an “international city” under outside administration.

5. They prevented renewed warfare over the contested city of Brčko, because it was eventually arbitrated under international administration.

6. They established a new constitution of BiH (Annex IV) with guarantees of human rights.

7. They provided for free and democratic elections, held successfully in Sept. 1996 under the supervision of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) headed by Ambassador Robert Frowick.

But what did the Accords fail to do?

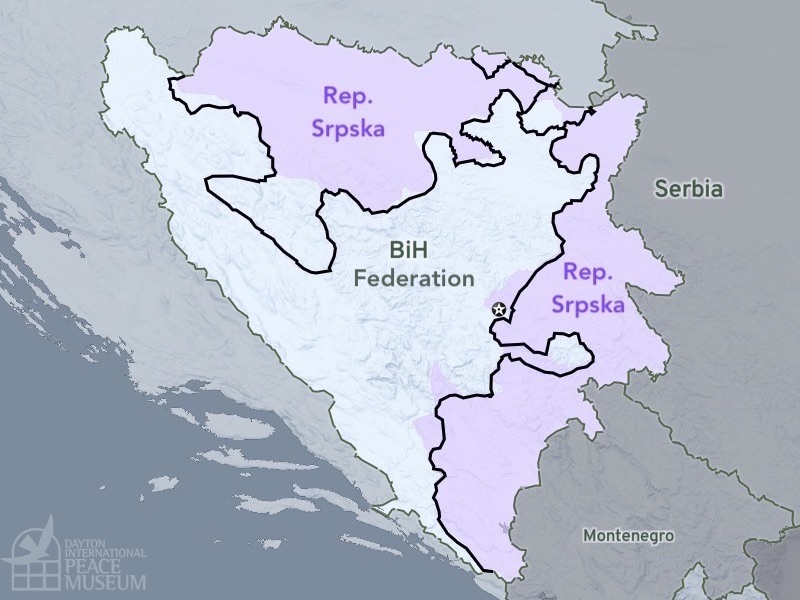

1. They did not restore the prewar boundaries of BiH. The Croats and Serbs kept the land they had seized during the war, for the most part.

Map of the Inter-Entity Line, dividing Bosnia-Hercegovina into republics and zones under a weakened central government. (CC-BY-SA)

2. They did not address the ethnic nationalism that had led to the war and which risked more violence, such as the war that broke out in Kosovo in 1998. In fact, ethnic divisions were enshrined in the Bosnian Constitution.

3. They did not establish a strong or united central government: the Presidency rotates among the three main ethnic groups every 8 months. Many governing powers devolved to the sub-republics of Republika Srpska and the BiH Federation.

4. They did not provide resources to re-establish the shattered economy or any continued support from the world community for rebuilding a country laid low by four years of war.

5. They did not even allow, much less require, NATO forces to arrest those leaders indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal.

6. They did not settle issues for the return of the 2 million refugees to their homes.

7. They did not establish methods for reconciliation after the ethnic cleansing and genocide of so many civilians. As the next button investigates, it was left to the people of BiH to figure out how to heal.

Even 25 years later, many of these issues are still sensitive challenges in Bosnia for completing the true meaning of peace.

How do you heal from a war like this?next page

Scholars of war-torn societies have written about the need for REDRESS. It is a human need to gain a shred of justice before most people can take the next step to forgiveness and reconciliation.

But how do governments provide redress for such massive trauma as what happened in Bosnia?

1. Being truthful:

One part of it is the chance to give testimony: to record for all time the truth of what happened. In some countries, this is accomplished by formal “Truth and Reconciliation Commissions.” For Bosnia, it was a Tribunal that served much of this function.

In May 1993, the UN realized the heights of the atrocities it had been ignoring for over a year in Yugoslavia. This led the Security Council to establish its first criminal tribunal since the WWII Nuremberg Trials. Distinguished judges all over the world were elected to serve on the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia: the ICTY.

Photo courtesy of the ICTY, CC-BY-2.0

Many victims’ groups travelled to The Hague to watch the proceedings and to serve as court witnesses to the worst atrocities. The record of this war is now beyond doubt.

next page▶

2. Consequences:next page

The work of the ICTY would be very slow: taking years to apprehend the accused, conducting cases and appeals very deliberately, reviewing every sentence, making every effort to give suspects a fair trial, not a political one.

The following people would eventually face consequences.

Among Bosniaks:

Chief of Staff of the Army of BiH

Rasim Delić was sentenced to 3 years for his failure, as a commander, to prevent the El Mujahed Detachment of the Bosnian Army from committing crimes against captured civilians and enemy combatants — actions which included murder, rape, and torture.

18-year old guard at Čelebići prison camp

Esad Landžo was sentenced to 15 years for murder, torture and other abuses of Serb civilians at Čelebići prison camp. In 2017, he appeared in a documentary ‘The Unforgiven,’ where he attempted to seek out his victims and atone for what he did.

...As well as three other Bosniak officers

Photos courtesy of the ICTY

◀prev

next page▶

Consequences among Croats:next page

Chief Commander of the Croatian Defence Council

Photo credit: [3]

Having overall command of that military force, Milivoj Petković was sentenced to 20 years for war crimes and ethnic cleansing of Bosnian Muslims.

General in the Croatian Army & Croatian Defence Council

Photo credit: [4]

Slobodan Praljak was sentenced to 20 years for his senior command over grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, violations of the laws or customs of war, and crimes against humanity. When he lost his appeal in 2017, he drank poison in the courtroom and died.

Prime Minister of the short-lived ‘Croatian Republic of Herceg-Bosna’

Photo credit: [5]

Jadranko Prlić was judged to have held ultimate political authority in that region of Bosnia, that he could have stopped the Croat forces’ concentration camps and crimes against humanity. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison.

...And 15 other officers

[3],[5] Photos courtesy of the ICTY, CC-BY-2.0

[4] Photo has the background retouched, a derivative of that of the ICTY, CC-BY-2.0

◀prev

next page▶

Consequences among Serbs:next page

President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Photo credit: [6]

Initially, Slobodan Milošević faced no consequences and enjoyed much of the credit for stopping the war. His Serbian government went on to pursue ethnic cleansing in the republic of Kosovo, causing another war in 1998. In 1999, the Tribunal charged him with war crimes occurring in Kosovo, and then—only later—added charges related to Croatia and BiH. He died of a heart attack in 2006, just weeks before the Court was scheduled to rule on his guilt or innocence.

Former President of Republika Srpska

Photo credit: [7]

In a plea bargain, Biljana Plavšić was sentenced to 11 years for one count of a crime against humanity.

Army Commander of Republika Srpska and

Former President of Republika Srpska

Photo credit: [8],[9]

General Ratko Mladić and Radovan Karadžić were sentenced for genocide at Srebrenica, violations of the laws and customs of war, and numerous crimes against humanity. Mr. Karadžić appealed his 40-year sentence, and the Court ruled it too lenient: raising it to life in prison. Gen. Mladić was given a life sentence. Expressing no remorse, he believes only his own people may judge him.

[ KARADŽIĆ CONVICTED 2016 ]

[ MLADIĆ CONVICTED 2017 ]

film clip: ICTY / The Irish Times (1.5 minutes)

...Plus 54 other convictions:

[6],[8],[9] Photos have their background retouched, a derivative of that of the ICTY, CC-BY-2.0

[7] Photo: Reuters (background retouched). Used under the principle of Fair Use for an educational purpose.

◀prev

next page▶

Although the ICTY did indict 161 different people (and convicted 90 of them), by no means did that serve justice to every perpetrator.

War refugees still remember the guards at other concentration camps, like Gabela and Dretelj, who have never stood accused. Some former brutalizers have continued their careers in city and county office up to this day.

25 years later, not even all of the dead have been counted from mass graves.

3. Apologies:

Several scholars point out that the simple act of a government apology can also ease tensions. There is great power contained in a leader’s admission that they know they did wrong.

Some people in Bosnia hold a different cynical opinion and would rather not talk about the past. “People should move on” — stop unearthing the mass graves of genocide, let the dead lie where they are. This misses the entire point of redress. Families re-bury their loved ones because they want to do so on their own terms, with a dignity that was denied by the murderers in camps. Each family needs that small amount of justice and reverence.

A short film by Ziyah Gafić explores the reburial of victims in 2010,

at the 15th anniversary of Srebrenica. (5 min)

4. The Power of Art:

Photo by Jennifer Boyer, CC-BY-2.0 (color is retouched from original)

Sarajevans used art to acknowledge but transform marks of destruction. In places where a mortar shell had once killed people, they filled the concrete scars with red resin, and the pattern it creates is known as a “Sarajevo rose.”

But over time, the roses will disappear as the asphalt is replaced.

5. Monuments:

In towns across BiH, all sides have placed monuments to commemorate people killed in local atrocities, to give survivors some peace and a place to grieve.

Images in the collection of the Dayton International Peace Museum, photographer unknown

But a monument by itself does not always lead to reconciliation. The more hopeful moments have been the rare times when the “other side” came.

For example, the Prime Minister of Serbia went to Srebrenica in 2015 to lay roses a second time — four months after the first time when people threw rocks at him. That humility took bravery, and showed he was serious. Likewise, in 2016 the Bosniak President Bakir Izetbegović visited a memorial for Bosnian Serbs in Kazani, saying “I should have come here sooner.”

◀prev

How short is the line from dehumanizing others ...to the start of violence?

The animosity behind the war in Bosnia had its roots in xenophobia. But it was not a foregone outcome that had to occur. As Yugoslavia broke apart, this was stoked by nationalist leaders who found it a useful way to gain power.

For example, it was in 1989 that Slobodan Milošević gave his famous speech about Greater Serbia “facing a battle” against historical enemies of the Serbs.

As animosity escalated in 1992, Orthodox Christians would refer to Bosniak Muslims as “the Turks” — although that language was plainly inaccurate and incendiary.

By 1994, Ms. Plavšić, the Vice President of Republika Srpska, would claim:

“It was genetically deformed material that embraced Islam. And now, with each successive generation it simply becomes concentrated. It gets worse and worse. It simply expresses itself and dictates their style of thinking, which is rooted in their genes.”

“It was genetically deformed material that embraced Islam. And now, with each successive generation it simply becomes concentrated. It gets worse and worse. It simply expresses itself and dictates their style of thinking, which is rooted in their genes.”

Do you ever hear hateful, xenophobic language about Muslims — or any other group — on social media? Or in your community?

So if we are going to learn the lesson of the Dayton Peace Accords...

Share this video

Share this video