These have always been a cosmopolitan crossroads

Bosnia-Hercegovina has always been coveted. Its first known settlers were Illyrians. We know them only from the ancient Greeks, who traded with them for gold, copper and tin, and from the Romans, who conquered them as part of their empire, starting before 100 BCE.

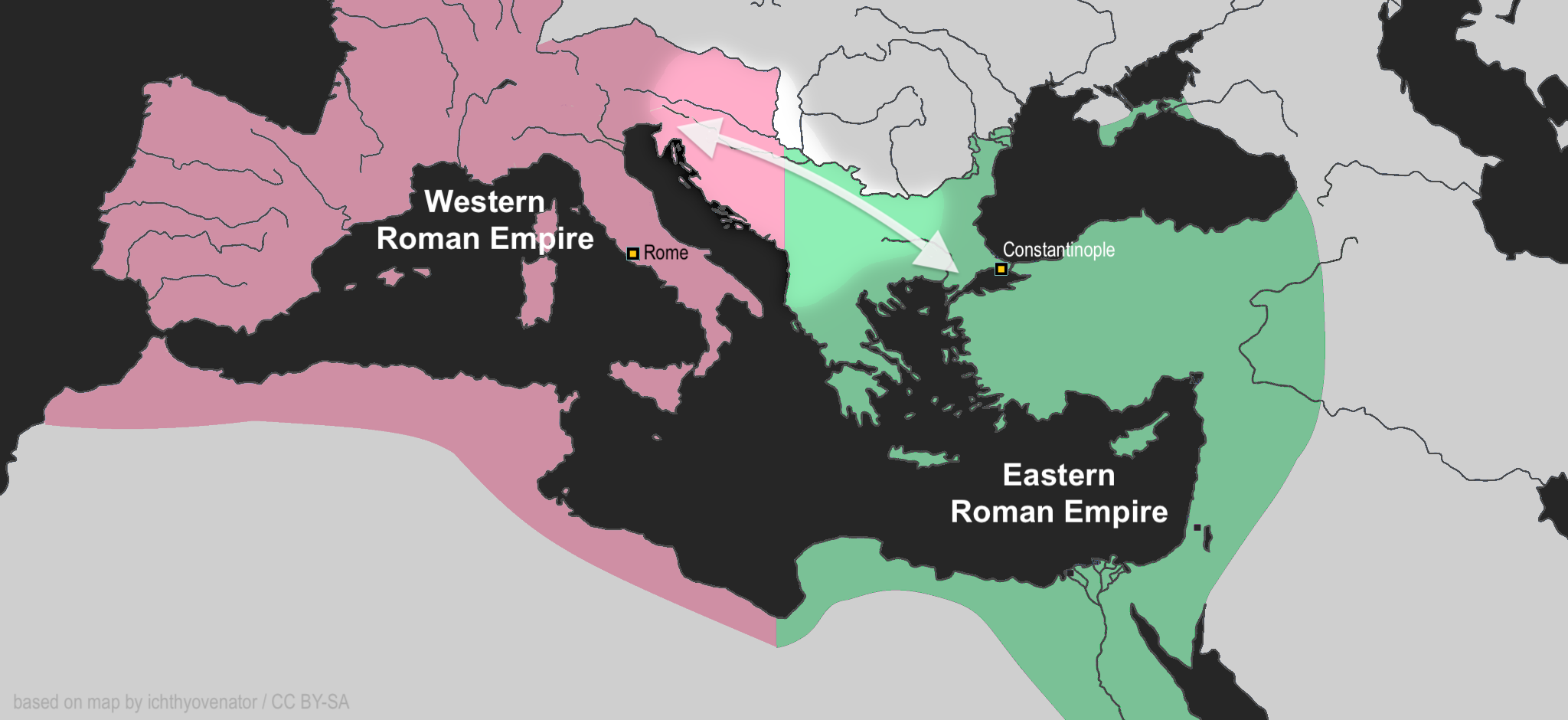

The Roman Empire, too large to govern, was divided into Eastern and Western halves in 286 CE, and each side had its own emperor. The eastern half, which included the Balkans, became known as the Byzantine Empire. It was richer and stronger than the Empire in the west and withstood attacks by “barbarians” much longer, although Visigoths and Alans raided and settled here.

By 814 CE, Slavs had also settled into what we now know as Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia-Hercegovina. All these various peoples practiced Christianity, which at that time in history meant Catholicism.

Meanwhile, Muslims were assembling their own empire under the Ottomans. They spread from the Middle East into Africa and parts of Europe. They conquered the Christians in the Balkans as early as the 1300s, but did not insist on converting their new subjects to Islam. Jews escaping from the Spanish Inquisition settled here in the late 1400s and found refuge. By then, the Slavs in the area had allied themselves with groups in Russia and converted to Orthodox Christianity, the first major break in that religion. Croat people remained mostly Catholic Christians.

By the 1800s, Austria expanded to the south and east and took over part of the Balkans, yet the southern area was still under the Ottoman Empire. By 1878, Serbia had been freed from the Ottomans and wanted to ‘free’ all Slavic peoples, including Slavs being ruled by Austria. This idea led Mr. Gavrilo Princip, a Serb, to assassinate an Austrian archduke and begin World War I.

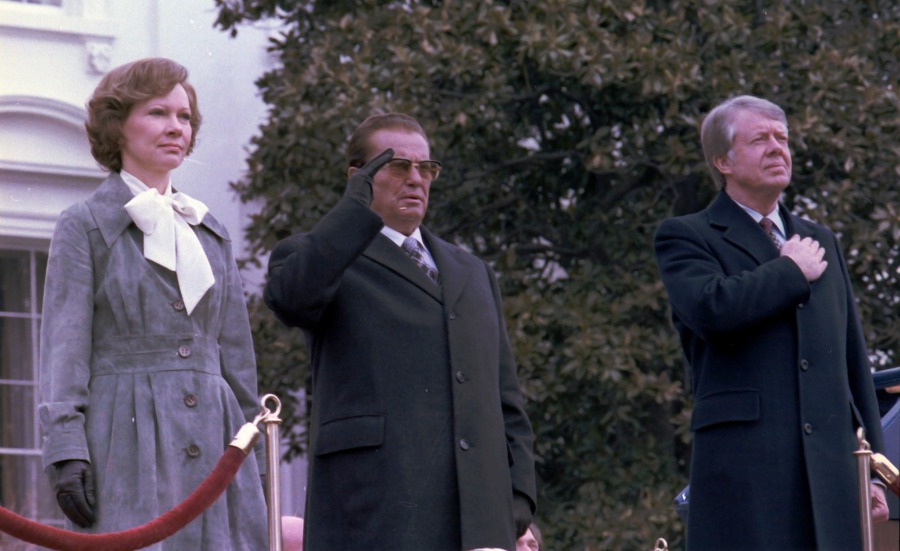

Austrian and German fascists ruled the Balkans during World War II. Josip Broz Tito led the resistance, and then ruled a new country at the end of that war: called Yugoslavia, meaning ‘land of the Southern Slavs.’ As a communist who broke ties with Russia, Tito’s motto was “Brotherhood and Unity.” There may have been tensions among the different ethnic groups in Yugoslavia, but Tito was able to suppress any outward conflict with his strongman grip on power.

Yugoslavian President Josip Tito visits the United States in 1978. Photo: US NARA

After Tito’s death in 1980, the cooperation among ‘the Southern Slavs’ broke down. The power vacuum gave rise to new, aspiring politicians.

By the dawn of the 1990s, this land had been home to a diversity of peoples for at least 1100 years, but new leaders were charting a different path. Slovenes wanted their own country from the Yugoslav republic of Slovenia. So did many Macedonians in the republic of Macedonia. Ethnic Albanians were only a minority and were lost somewhere in all this maneuvering. Croats chose a nationalistic leader to carry Croatia to independence. And by alluding to certain enemies, a politician from Serbia proclaimed the destiny of all Serb people was to live in one state — that wherever they lived was, by birthright, “Greater Serbia”.

Continue to next screen: